The Changing Face of Disability

Friday 24 April, 2020 Written by Natasha Christou

DISABILITY - Numbers of those with disabilities are rising and higher in state pension age adults partly because the population is living longer, increases in chronic health conditions, and the majority of disabilities occurring later in life.

The Changing Face of Disability Over Time

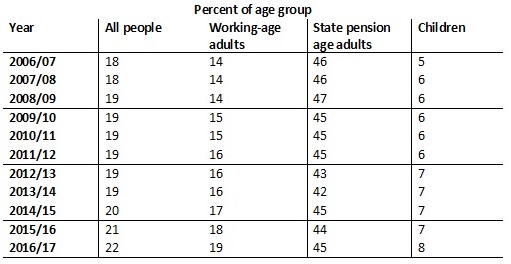

In the UK, there were 13.9 million people with a disability recorded in 2017, which equates to about 22% of the UK population; 8% being children, 19% being adults, and 45% being adults of pension age. Disability has changed tremendously over the last 80 years, with change really occurring during the last few decades. Changes to legislation, attitudes, and services have improved people’s lives drastically — people with disabilities are disabled in society because able bodied people are the norm and so the world is built around their abilities. For example, a person’s disability is an interaction of their health condition, personal, and environmental factors such as attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social supports. Changes over time in society have provided people with disabilities with more opportunities and better daily functioning, so it’s important to accommodate their needs in every way possible.

A disability can present itself in many forms, including physical impairment, mental and learning disabilities, to terminal illnesses reducing a person’s abilities. Here, we’ll take a look at the changing face of disability over time.

How have disability figures changed over the years?

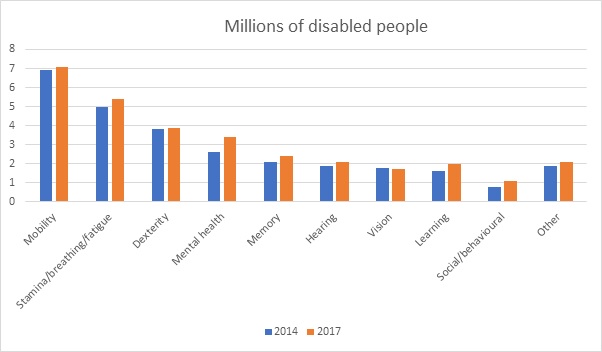

According to 2017 data from the UK government, the most common type of disability is related to mobility, with 51% of those with disabilities being mobility related. The same trend can be seen for 2014, with 6.9 million people with a mobility disorder — significantly higher than the other kinds of disabilities in the table below. The disability that is least common in both 2014 and 2017 is social and behavioural, including attention deficit disorder, autism, and anxiety. The disorders have increased similarly, ranking the same in 2017 as they were in 2014. A large proportion of those with disabilities are mental health and behavioural problems, which have been found by research to be one of the main causes of the overall disease burden across the world, with 7.8% of British people being diagnosed.

Numbers of those with disabilities are rising and higher in state pension age adults partly because the population is living longer, increases in chronic health conditions, and the majority of disabilities occurring later in life.

How have disability definitions changed?

The 2002 International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (IFC) defines disability as “an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions”. In 1980, the ICF definition for disability was dependent on sex and culture, as well as having separate definitions for impairments, disabilities, and handicaps. Revising the definitions to become more inclusive has helped create individual profiles of people. Instead of focusing on their limitations, it focuses on how their abilities can be enhanced by factoring in environment and personal ability. The 2002 definition has been radically updated to incorporate the stress on health and functioning — previously, disability began where health ended, and people were placed in a different category — something society is moving away from.

Understanding how disabilities affect each individual person’s functioning allows improved services, treatment, and rehabilitation for those with long-term disabilities, as well as acceptance and empathy. Definitions of disabilities have also become more inclusive to incorporate invisible disabilities such as mental illnesses and brain injuries.

In 2010, a report highlighted how disabled people were suffering immense restrictions in transport and access, leading to anxiety and low confidence — a shocking finding in the 21st century. In 2019, the Department of Transport extended blue badge eligibility to support those with hidden disabilities, including people who can’t walk without significant psychological distress or risking serious harm — the biggest change to the scheme since its introduction in 1970. This, combined with Motability vehicles, will help support those with a range of disorders to travel and socialise without unnecessary concern, making it easier to access parking closer to facilities. Although this is a positive change, it shouldn’t have been an issue only resolved in 2019.

Is there more focus on mental health and behavioural problems?

Depression and anxiety have been receiving a lot more focus over the last few years, with an active attempt to remove stigma around these illnesses. The concept of disability has shifted radically, originally, the focus on disability was what we could see — an obvious physical limitation, which excluded those with hidden disabilities who needed help too. This has been incredibly important as hidden disabilities can be extremely debilitating and affect someone’s life as much as a physical disability.

As far back as 1670, those with hidden disabilities and mental health issues were placed in “madhouses”, with no structure in place to inspect or regulate them. Those with symptoms were locked away from the rest of the world and left in neglected environments because there wasn’t an understanding. Until the 18th century, psychiatry began to advance, and the way those locked away were treated changed as people understood more about mental health and hidden disabilities.

In 2000, one in four people were receiving treatment for mental health, whereas by 2014, this increased to more than one in three. It’s likely that statistics of mental health have risen over the years because increased awareness in the media are helping people realise that they have problems and need help. Many people don’t recognise the symptoms when they’re not aware of what’s happening in their mind isn’t the norm. Mental health is now viewed as an illness of the mind, like disability is an illness of the body. It’s important to remember just because someone’s disability isn’t visible, it doesn’t mean that it isn’t there and the person doesn’t face struggles day-to-day.

How have attitudes changed towards disabilities?

There has undoubtedly been progression in attitudes to disabilities, but we’ve still got a long way to go. When newly disabled British soldiers returned from the First World War, attitudes began to change, advances in prosthetics happened, special housing was built, and employers were encouraged to employ disabled workers.

However, research from Scope, a disability equality charity, shows that one in three disabled people felt that there’s prejudice against those with disabilities in 2000. 37% of disabled people and 34% of non-disabled people agreed about prejudice about disability, whereas in 2017, 32% of disabled people agreed with this, whereas only 22% of non-disabled people did. The gap grew, showing an increased divide in attitudes and opinions. Scope also found that 20 years ago, 38% of disabled people said they were called names and 59% were stared at, whilst 2014’s figures were 17% and 30%, respectively.

Perhaps attitudes have changed towards opinions of prejudice as, according to the Labour Force Survey, disabled people are more likely to be employed now than they were in 2002, with more opportunities available for those with disabilities. However, 46% of disabled people were employed in 2012, which is only up 7% in 2020. To help, the government has aimed to get one million more disabled people in work with funding for special equipment and software. Although there has been an increase in comparison to 20 years ago, disabled people are still significantly less likely to become employed than non-disabled people — 46% of disabled people are in employment in comparison to 76% of non-disabled people. Although legislation is in place to oblige employers to make fair workplace adjustments for workers, there is still a significant struggle for those seeking work.

There has been a significant increase in the number of people with mental health illnesses. Over the years, there has been focus on raising the awareness of mental health disabilities and removing stigma, with more and more people recognising the symptoms and seeking help. Many years ago, those with mental health disabilities were ostracised and viewed negatively. Research from 2016 found that there’s been a 15% increase in those willing to live with someone with mental health issues, showing improvement in attitude.

How has government expenditure changed?

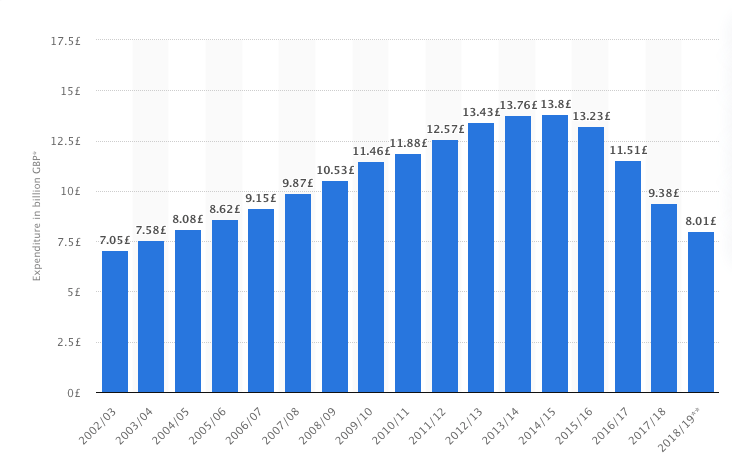

Surprisingly, government expenditure has been reduced by £5 billion over the few years following austerity and cuts. Expenditure on welfare benefits for the UK’s poorest families have shrank, hitting vulnerable people the hardest. It is well known that people with disabilities have extra costs, on average £570 a month, causing struggle when prices and living costs are rising.

Disability has changed significantly over the years, with improving attitudes, definitions, and access, however reduced government expenditure is causing difficulty for many. A collective effort to continuously improve the lives of those with disabilities with changing times will be hugely beneficial.

Sources

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health

https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf

http://www.ashfordstpeters.nhs.uk/19th-century-mental-health

https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/1914-1945/

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/aug/23/learning-disabled-people-need-work-opportunities

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7540/

ABC Note:

Rt Hon Stephen Timms MP, Chair of the Work and Pensions Committee, recently said:

“Hearing from people with first-hand experience of the benefits system is a crucial part of our scrutiny of the DWP. It’s clear from what we’ve heard that DWP staff are working very hard and have made great strides in adapting to the unprecedented strain on the benefits system.

“But we’ve also heard from people who are still facing serious difficulties. Disabled people have been particularly hard hit: their living costs have gone up, but their benefits have stayed the same. And there’s an urgent need for more clarity for people who are self-employed. We hope that Ministers will look carefully at what people have told us, and make changes.

“It would be easier to understand how the system is working in practice if DWP were to publish more information. We’ve asked for quite basic facts—such as how long people are waiting on the phone—but had no answers. Our survey has attempted to fill in some of the gaps, but there is no substitute for the official data. The Department must now follow the very clear instruction of the UK Statistics Authority and make this data available to the public.”

The Committee yesterday questioned Ministers and officials from the DWP on how the Department was handling the unprecedented increase in applications for Universal Credit and its overall approach to supporting people claiming benefits.

ABC Comment, have your say below:

Leave a comment

Make sure you enter all the required information, indicated by an asterisk (*). HTML code is not allowed.

Join

FREE

Here